Last Train to Mouldsville

Dr Michael Brown, Curator Music at the Alexander Turnbull Library has written a blogpost for us about preservation:

The recent revelations about Universal Music’s disastrous 2008 vault fire, in which an estimated 170,000 master tapes were lost, have highlighted just how vulnerable these and other unique tape recordings can be. But the threats to such artefacts need not be so spectacular as a roaring inferno. There are a range of slower-moving but still serious dangers which, in many cases, can be guarded against through careful storage. This blog gives a brief rundown of some simple measures you can take to protect your magnetic tape recordings.

Open-reel tape recordings in Alexander Turnbull Library, showing shelves with earthquake bars. Photo: Michael Brown.

Before considering what tape media needs to be protected from, though, it’s worth reiterating why such recordings are so important in the first place.

Audio masters represent the best-quality sources for music recordings. The audio is typically far more detailed and richer in frequency saturation than what ends up on a consumer format such as vinyl, CD, or download file. Embodied in the magnetic particles of the tape binder-layer is the greatest amount of original sonic information there will ever be about a particular recording. As such, masters are the ideal starting point for any later remasters or remixes. They may also contain unreleased songs, outtakes, and alternative mixes, all potentially valuable for creative reworking or supplementing future reissues, or for the music scholars of the future. The same applies to more informal recordings such as demos, audience recordings, and tapes of rehearsals or jam sessions.

Yet magnetic tapes are vulnerable to all manner of agents of deterioration. These include the 10 agents identified by archivists and conservators (list taken from the Canadian Conservation Institute):

Physical forces (e.g., impact, vibration, pressure)

Fire

Pests (e.g., microorganisms, insects, rodents)

Light, ultraviolet and infrared

Incorrect relative humidity

Thieves and vandals

Water

Pollutants

Incorrect temperature

Dissociation (i.e., loss of information about objects)

All of these can contribute to the deterioration or loss of audiovisual tapes and the content they contain. In examining tapes for potential inclusion in the Alexander Turnbull Library over the years, the consequences of the ten agents have sometimes been all too apparent: broken reels, crushed video tape shells, creased and tangled tapes, contamination from toxic household chemicals, layers of dust and dirt, insect nibbling, fly spots and guano, distorted tape packs from water spills, and - of course - mould infestations, ranging from the single white spot through to thriving colonies of furry white-green. Tapes can suffer several of these maladies at the same time.

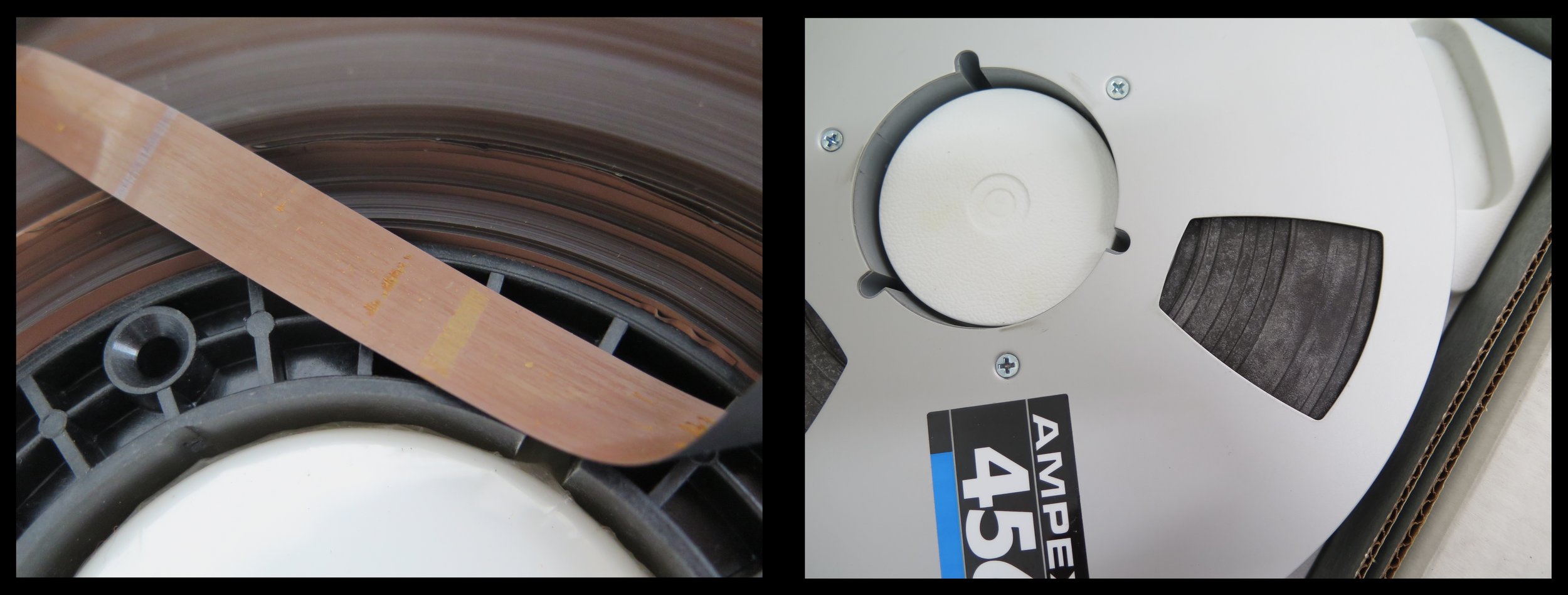

Audio tapes in poor condition, including binder damage, creasing and uneven tape pack (left) and mould on tape pack (right). Photos: Nick Guy.

Repairing and restoring a damaged tape to a playable state can require hours or even days of conservation work. In some cases, with all the best efforts and intentions, intervention may be too late. The content on such a tape may be severely degraded - so much for that master-quality audio! - or lost forever.

It’s worth remembering, too, that magnetic tape suffers from two additional, unique risks of its own. The first is chemical instability arising from historic tape formulations, resulting in sticky-shed syndrome and other problems (check out this article by Richard Hess for a discussion). The second is technological obsolescence: the ever-decreasing availability of playback machines, spare parts and service engineers. Some commentators predict we have until only 2025 before large-scale digitisation will become extremely costly due to the challenge of sourcing working legacy gear (check out the discussion paper Deadline 2025).

Given this ‘perfect storm’ of risk around tape preservation, any measures that the holders of audio tapes can adopt to protect them from the more mundane hazards will be critical in ensuring their survival into the future.

Of course, few people will be able to exercise total climate control over the environments in which they store their tapes. But even a simple intervention such as placing an open-reel in a plastic bag within its tape box can make a world of difference. Recently, we came across a collection of tapes that had been stored in the same location for many years. Although the same family of spiders seemed to have set up shop in the boxes at some stage, the bagged tapes were in virtually pristine condition, while many of the unbagged were on the last train to Mouldsville.

The following sections - adapted from the National Library of New Zealand’s webpage about caring for your sound recordings - give some basic guidelines about caring for your audio tapes.

Storing tapes

The best place to keep sound recordings is somewhere cool, dark, dry and well ventilated, such as a cupboard or shelf. Keep sound recordings:

off the floor;

where they will not be constantly handled or disturbed; and

away from sources of light, heat and water.

A collection of sound recordings can be heavy, so make sure that they are stored on strong and secure shelving.

Store tapes upright. Laying them flat will cause the tape to become distorted. Avoid stacking tapes one on top of the other, as this creates a lot of weight and will damage those at the bottom.

Each tape should be in an individual box and both the tape and the box should be labelled with the contents of the recording, thus helping prevent dissociation. An open-reel tape can also be placed within an unsealed bag made of polyethylene or polypropylene (both relatively inert) inside its tape box. This gives an added layer of protection from temperature fluctuations and humidity, although it’s important not to seal the bag as this might create a micro-environment.

Ensure cassettes and videos are stored fully rewound.

Magnetic fields can erase the content from tapes. Store tapes away from anything that can create magnetic forces, including TV sets, computers, cellphones, and other electrical appliances, electrical transformers and power boxes.

Careful handling

Handling is a major cause of damage to sound recordings, so it is important that they are handled as little as possible and that they are always handled gently.

The surface and edge of the tape in cassettes and videos is easily damaged and so the tape itself should never be touched.

It is important to handle reel-to-reel tapes by the centre or hub. Reel-to-reel tapes are more at risk than other tapes, as they are not protected by a case.

Playing tapes

Repeated use of tapes will cause wear and damage. Handle and play original recordings as little as possible.

Avoid pausing tapes as this causes stress and damage to the tape. Going from rewind to fast forward without pushing stop will also cause tension and damage.

Store cassettes and videotapes in a fully rewound state to avoid creating tension at one point of the tape.

Copying and digitising tapes

Making a copy is often the best option for preserving a sound recording. The benefits of copying include:

reducing wear on the original

creating extra recordings in case of a disaster or theft

creating new copies in formats that can be played on current equipment.

For unique sound recordings, it’s a good idea to have a master copy and a listening or viewing copy. The master copy should be to the best standards possible, and used only if it is needed to produce another copy. Keep the two copies in different buildings to reduce the chance of the recording being destroyed in a disaster.

Copying sound recordings is a time-consuming and technical process. The work often needs to be done by a specialist company, and can be expensive. You may want to consider applying for funding for a copying project. There are a number of agencies that grant funding for such projects (see this webpage for information about funding agencies). Only use a reputable company for making copies.

Some further resources

Caring for your sound recordings (National Library of New Zealand)

Caring for videotapes (Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision)

Handling and Storage of Audio and Video Carriers TC 05 (International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives)

Ten agents of deterioration (Canadian Conservation Institute)

Radio programme on audiovisual preservation (Radio NZ)

Thanks to Nick Guy for assistance with this blog.